This year’s Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences, popularly known as the Economics Nobel has been awarded to Claudia Goldin for “for having advanced our understanding of women’s labour market outcomes”.

The Harvard University professor’s Nobel citation lauds her pioneering work and said that her research “provided the first comprehensive account of women’s earnings and labour market participation through the centuries”. It added, “Her research reveals the causes of change, as well as the main sources of the remaining gender gap.”

Goldin’s work comprises decades of research where she has collected and studied over 200 years of data from the US to explain the gender pay gap and how employment rates of women have changed over the years.

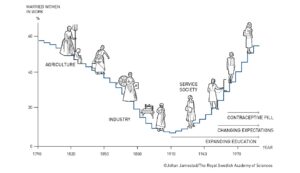

Through her research, Goldin has shown that unlike the common perception, women’s participation in the labour market has not seen an upward trend over the years as the economy progresses. Instead, as the economy moved from agriculture to industrial to services-driven, women’s participation has taken a U-shaped curve. Goldin explains that this change is attributed to the structural change in society and evolution of women’s role expectations towards family and home. But social norms and discriminatory laws “continue to determine both the extent and the speed to which female employment rates increase”.

Source: Nobel website

Post the 1970s, there was a social shift with advancement of technology, growth of the services sector and an increase in the education level of women. One of the reasons for this investment by women in their education was the invention of the birth control pill. Goldin and Katz show that contraceptive pills gave women the power to delay marriage and focus on their careers.

In her Richard T. Ely Lecture, Goldin talks about a “quiet revolution” (also the title of the lecture) that has shaped women’s employment. She says that women’s involvement in the economy was a transition from evolution to revolution. “It was a change from agents who work because they and their families “need the money” to those who are employed, at least in part, because occupation and employment define one’s fundamental identity and societal worth. It involved a change from “jobs” to “careers,” where the distinction between these two concepts concerns both horizon and human capital investment,” she said. This revolution was quiet for the “grand transformation”that altered women’s employment, education, and family.

Goldin’s 2014 paper, “A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter”, goes on to explain that although the gender gap has reduced, it still exists despite an increase in education levels. “Quite simply the gap exists because hours of work in many occupations are worth more when given at particular moments and when the hours are more continuous,” Goldin points out.

In her book Career and Family (2021), Goldin described the fight for a more inclusive workplace while tracing women’s century-long journey to reduce the gender gap. She also brings up the issue of equity in the household. Goldin hopes for a future where women have a career and a partner who wants what they want.

In an interview, she says that the “flip side to gender inequality is couple inequity”. When children come into picture, one parent has to be “on-call” which would need more flexibility in work hours or a less demanding job. “Why can’t dual-career families share the joys and duties of parenting equally? They could, but if they did, they would be leaving money on the table, often quite a lot. The 50-50 couple might be happier, but would be poorer,” she adds. Talking about the way forward, Goldin states, “The route out of these inequities is to lower the cost of workplace flexibility and childcare. The first may be happening with workplace changes that have occurred during the pandemic and the second is gaining political momentum. Bringing the men along in a host of ways is another part of the solution.”

Gender Gap in the world today

Goldin’s Nobel is a stark reminder of the long road ahead to gender equality. According to the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Global Gender Gap report 2023, while the world has closed 68.6% of the global gender gap, it will take 131 more years to achieve gender parity. Saadia Zahidi, Managing Director of WEF said, “Women continue to bear the brunt of the current cost-of-living crisis and labour market disruptions. An economic rebound requires the full power of creativity and diverse ideas and skills. We cannot afford to lose momentum on women’s economic participation and opportunity.”

According to McKinsey’s “Women at Workplace” report, while the representation of women in leadership positions has increased, they are still under-represented at all levels.

Relevance of Goldin’s research for India

India’s economic development didn’t trace the same trajectory as the US. Unlike the US, it went from agriculture to a services-driven economy. But Goldin’s research still holds a lot of relevance for India.

Reflecting on the Nobel for Goldin, 2019 Nobel laureates Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee in a blog wrote, “The obligations placed on married Indian women at home (between running the home and taking care of the children and the elderly) are so demanding that a regular job outside of the home is hard to manage. But unlike in the US a hundred years ago where women worked till they got married, even young unmarried women are missing in the Indian work scene, the combined result of parental paranoia and the very real lack of physical security in and outside the workplace.”

The Government has recently released the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) for 2022-23. According to the survey, the labour force participation rate (LFPR) for women has gone up over the years with two notable spikes – 2019-20 (26.3%) and 2022-23 (31.6%). This trend suggests that women are being pushed in the labour force to bolster the financial condition of their households especially as domestic work. This has made measuring the female labour in the economy very difficult. While PLFS is based on a survey, women still form a small percentage of the formal workforce or white-collared jobs. Care work and other household work done by women also doesn’t get documented.

In another report, Nirmala Menon, CEO and founder, Interweave Consulting said, “In an era of rapid technological advancements and increased access to education, women today have become quite aspirational and aware. However, in the Indian context, societal norms have struggled to evolve at a parallel pace with technology. Consequently, while women’s aspirations grow, they still have to grapple with balancing home and work responsibilities, often without significant contributions from men.”